“Why?” is possibly the worst question you can ask someone when you want to understand the reason for their decisions.

I’m sure you’re perplexed by that statement. You say, “I already know I shouldn’t take answers at face value.” My point is that in your quest to find the reasoning behind the answers, you may unintentionally lead yourself astray from the real information you need.

I often have the need to ask “why?” in my work during usability testing, interviews, or getting design feedback. “Why do you like design A versus design B?” “Why does pink not work here?” “How did you know to click on that button?” Answers to those questions really help me do my job.

Unfortunately, humans are bad at introspection, so the explanations we give are not always valid. You can usually believe someone’s decision (ex. “I like the blue socks better than the red ones.”). But when you ask for an explanation for why she made that decision, the reason may not be related to this specific incident (ex. “I like blue better than red.” versus “The red is too strong for my white shoes.”). In fact, believing someone’s explanation could lead you down the wrong path altogether.

What underlies this conundrum? And what should you use instead of “why?” I think a little experiment will help you understand the trouble “why” can create.

A little experiment

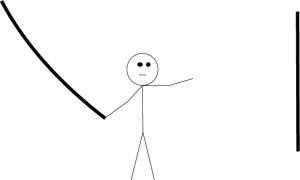

Let’s say I ask you to take part in my little experiment. I bring you into a room with two ropes hanging from the ceiling, like below.

“Your task,” I say, “is to tie these two ropes together. Go.” Instinctively, you try the naive solution. You grab one rope and pull it towards the other, but it’s just not long enough for you to grab both at the same time.

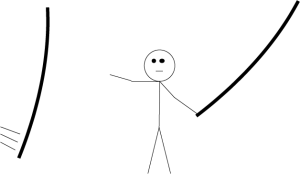

You can’t quite figure it out. I walk by the ropes, accidentally causing it to swing just a little. A few seconds later, you get an idea to start swinging one of the ropes. While it’s swinging, you grab the other rope and pull it towards the first one.

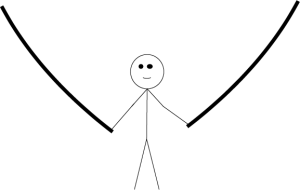

When the first one swings back, you catch it and tie the ropes together.

Then I ask you, “how did you know that was the solution?”

Time-out for science

This was a real experiment conducted in the 1930s and reanalyzed in a famous paper “Telling More Than We Can Know” by Nisbett and Wilson published in the 1970s.

There’s only one reason that explains how you got over your mental hurdle to solve the rope puzzle: I nudged the rope just a little. That means I’m expecting to hear only one answer from you when I ask my question: “I saw the rope swing just a little bit, and that sparked an idea.”

Unfortunately, people in this experiment gave anything but that answer: “I thought of monkeys swinging through the jungle.” “I was reminded of a trapeze act I saw at the circus as a kid.” “When I was in Hawaii, I did a rope swing into the ocean.” After being pressed, about a third of participants mentioned seeing the rope move. That means two-thirds of them had no idea what really triggered their answer.

This was one of several experiments that Nisbett and Wilson re-evalutated. Their conclusion was that we have little or no introspection into our cognitive processes. Further experiments proved that we have some introspective capabilities but it is very limited.

The impact of our limited introspection

As much as we think of ourselves as rational, self-aware beings, we are not fully aware of our decision making processes. The extent of this awareness depends on the individual and the circumstances.

To oversimplify, the kinds of answers people give in response include:

- The real answer – It’s possible that you’ll get the true justification for that person’s decision. In the rope swinging experiment, you would hear this as, “I saw the rope swinging, and that triggered an idea.”

- Shared knowledge – A plea to information or theories that are public knowledge or known to the group. “Everybody knows that you swing a rope, so that’s what I did.”

- Personal experience – The person will use their own beliefs, knowledge, or experiences as their answer. “I remember swinging on a rope swing as a kid.” That might have actually happened, but it’s not what triggered his answer.

When someone answers your “why” question, it could be the real answer, it could be something they pulled from their memories, or it could be something else completely different.

And this gets to the heart of the dangers of asking “why.” The response you get could send you down the wrong track. For example, take this (fake) usability test snippit:

You: Did you have any trouble filling out the form?

Subject: Yeah, the button was a problem.

You: Why?

Subject: It wasn’t clear what it does.

Actually, the reason why is that the button is blue, and the subject secretly hates blue ever since his third grade soccer team lost the city finals to a team wearing blue jerseys. But there’s no way to know that from his answer. His comment sends you on a wild goose chase to redesign that button due to someone’s vendetta against blue.

Similarly, imagine you’re getting feedback about your research into a new product:

You: …and based on our interviews with customers, they want a mobile version of the app.

An executive: I don’t think that will cut it.

You: Why?

An executive: That didn’t work for our competitors, and it won’t work for us.

It’s more likely that the executive has other priorities in mind or that he is biased against mobile apps, but the answer that came to mind first was “it didn’t work for the competition.”

Yes, you shouldn’t take answers at face value, but many people use “why” as a way to cut to the real answer. The answers that people give to “why” may take yourself off the path towards the real answer due to these limits on our introspection.

If I can’t ask “why,” what should I do?

First, you can usually believe the person’s initial decision. Imagine you’re choosing two pairs of socks and you immediately like the blue one more than the red one. You can give any reason you want for liking the blue one; nothing will shake your conviction that it is the superior pair. Same thing goes for other decisions. If someone dislikes your design, then they don’t like it. Accept their decision that your design has problems regardless of the reason.

Next, be careful not to ask justification-seeking questions. The questions, “why did you click on the games tab?” “how did you choose games next?” and “what drew you to click on games?” are really the same question. Any answer when asking about a person’s internal state during a decision is suspect by default.

Instead, try asking questions related to the action just taken. For the person who chooses “games” among several options, the most likely reason is because he likes games. “Do you like games? How much do you play them?” Questions of that sort will quickly prove your assumption and provide valuable information about your subject.

Similarly, if someone doesn’t like a design, you could ask questions like ,”what were you expecting to see?” or “how does this compare with [some other design the person liked]?” You could even try a more open-ended prompt like, “tell me more about that.”

Also, you can ask the individual to give an example or tell a story instead. For example if you’re researching video editing software users, you might be tempted to ask, “why do you need video editing software?” A much better question would be to ask for a specific time when they used it. “Tell me about the last time you used video editing software. What prompted you to use it?”

Stay on your toes, and think hard about the information you want to get back from your next question. You can usually come up with a better question than “why?”

This means something

I find great solace in these results for a few reasons. First, it justifies the need for psychologists and psychiatrists. These sciences are concerned with helping people live better lives by understanding our thought processes. Humans are poor at introspection, so it’s helpful to have someone objectively look at your actions and help you understand how you chose them.

Also, it’s good for your relationships. Say you’re arguing with your significant other and spout something mean like, “at least I’m not towheaded!” Then she gets all weepy and says, “why would you say something as horrible as that?” You can answer, “I don’t know, but I know why I don’t know.”* Be thoughtful when trying to understand someone’s justification for a decision. Nobody is fully aware of why you do the things you do.

Finally, this research justifies the work of designers, ethnographers, and similar professionals. Much of what we do is based on our understanding of the individual(s) we study. It’s hard work; asking good questions is just a small part of what we do. That’s why capable professionals in these fields are worth every cent you pay them.

Take this to heart the next time you start a new project or when you’re interacting with a friend. Even though humans suck at self-reporting our justifications for decisions, you can still get the information you need without asking “why.”

Coda

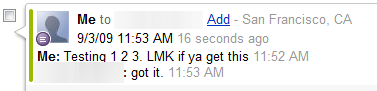

For my final project at UC Berkeley, a group of us studied Berkeley freshmen and how they used technology in their lives. Among the many topics we covered, we asked about their habits using file sharing software. No surprise — nearly all of them did it.

The next logical question we asked is, “why do you use file sharing software?” The answers were all over the map. “I don’t want to help the big music moguls.” “I don’t have the money to buy it.” “It’s free!” Reflecting on that now, “why” was a poor question to ask.

I hope your endeavors in your own research are better for this tidbit of thought.

*Don’t try this in a real argument. It doesn’t work.